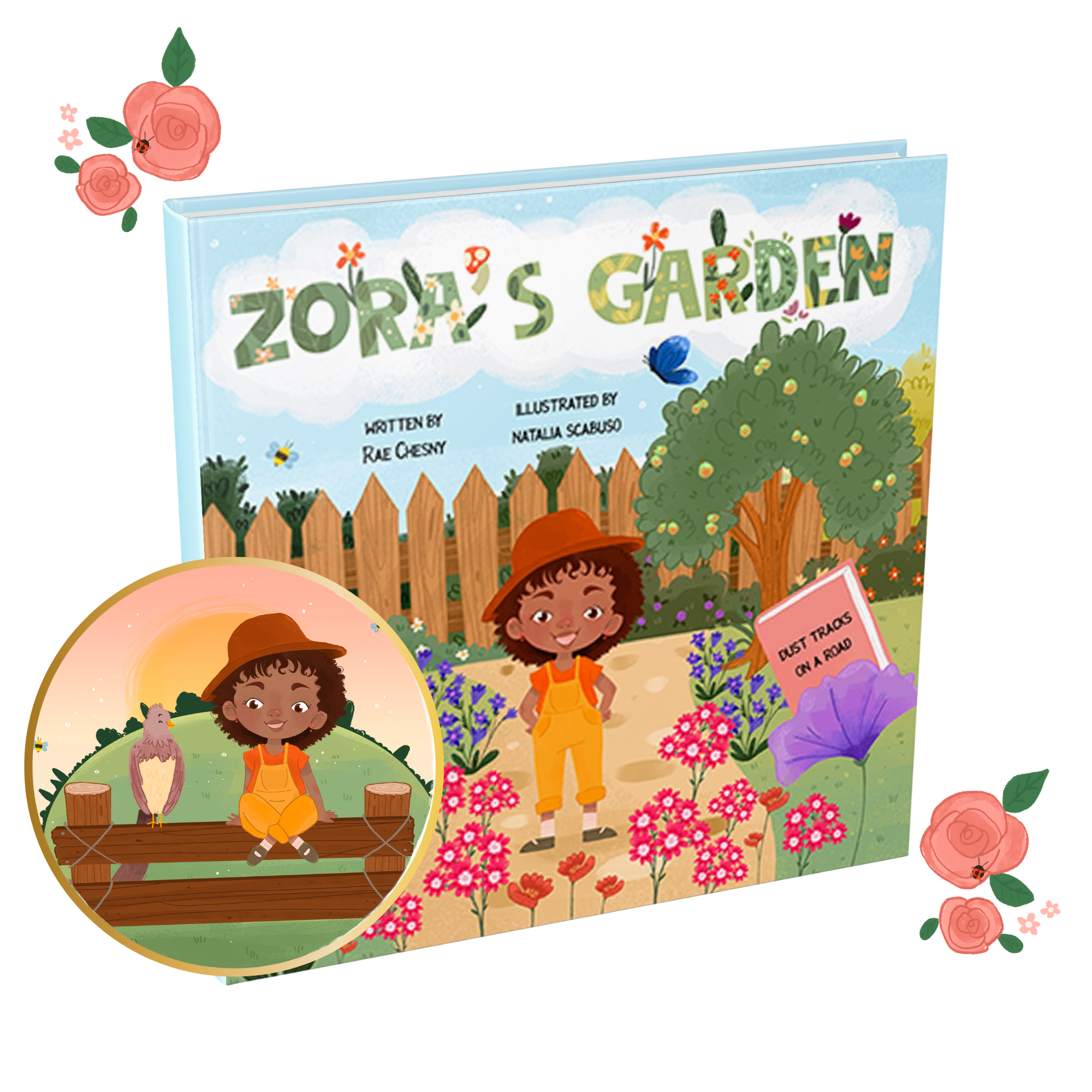

Inside the Book

In Zora’s Garden, the great and incomparable Zora Neale Hurston is imagined as a child, curious and observant, learning the magic of storytelling. Blending research with imagination, the book explores the book celebrates how stories take root to inspire young storytellers everywhere.

Here’s a sneak peek inside.

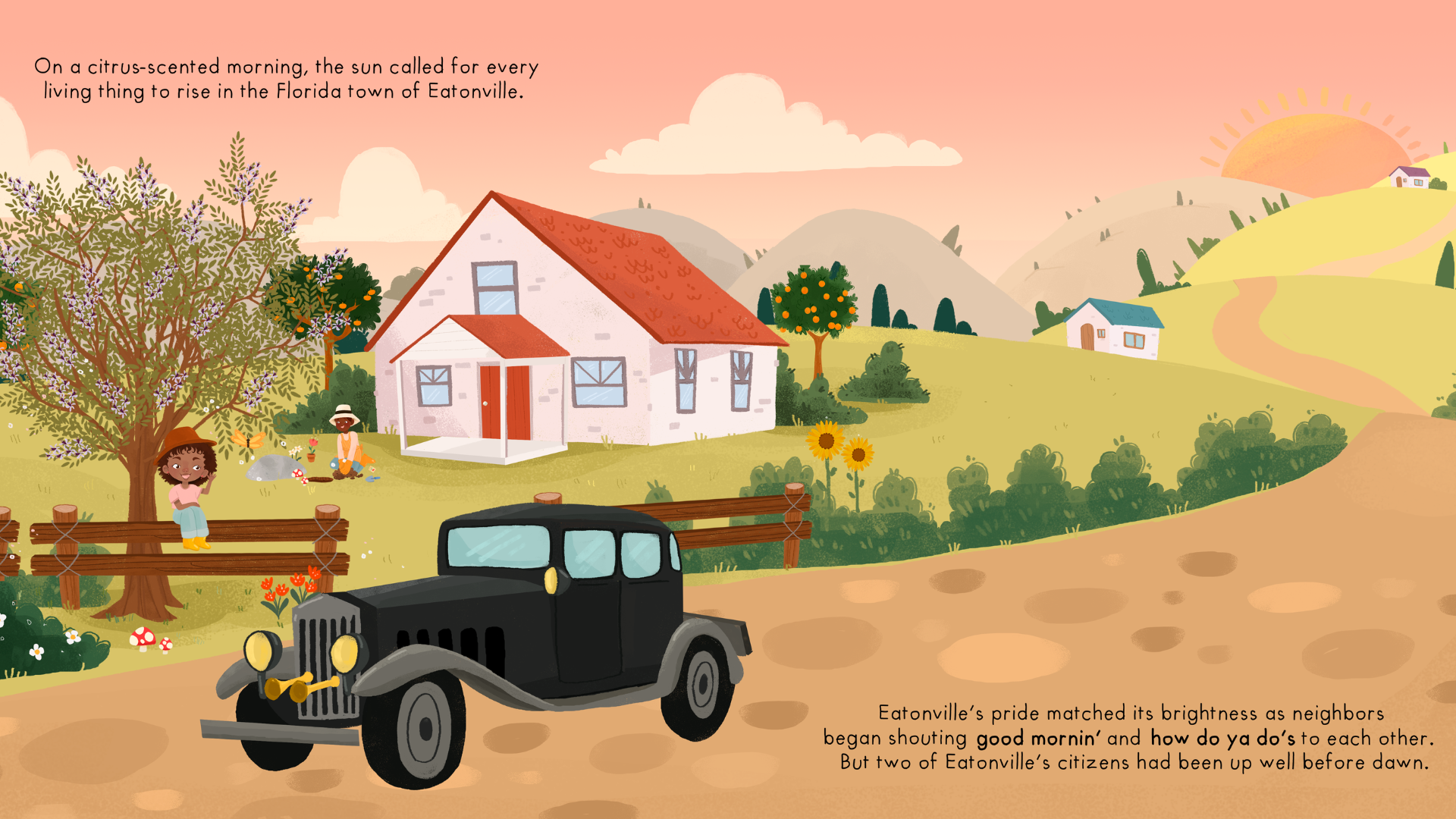

Zora’s Garden: Setting

Zora’s Garden is set in Eatonville, Florida, the town Zora Neale Hurston loved and wrote about throughout her life. Eatonville was the first incorporated Black towns in the United States, and it shaped how Zora understood freedom, community, and belonging.

Although Zora Neale Hurston was born in Alabama, she often spoke of Eatonville as the her birthplace. In many figurative ways this it true. It was the place where she truly became herself surrounded by Black teachers, leaders, neighbors, and storytellers, and where her imagination was nurtured long before she ever put pen to paper.

By choosing Eatonville as the setting for Zora’s Garden, the story honors the place that Zora herself immortalized in her writing. It invites readers to step into a town alive with voices, sunlight, and possibility, and to understand how a child’s surroundings can help shape a lifetime of stories.

I was born in a Negro town. I do not mean by that the black back-side of an average town. Eatonville, Florida, is, and was at the time of my birth, a pure Negro town—charter, mayor, council, town marshal and all. It was not the first Negro community in America, but it was the first to be incorporated, the first attempt at organized self-government on the part of Negroes in America.

—Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road

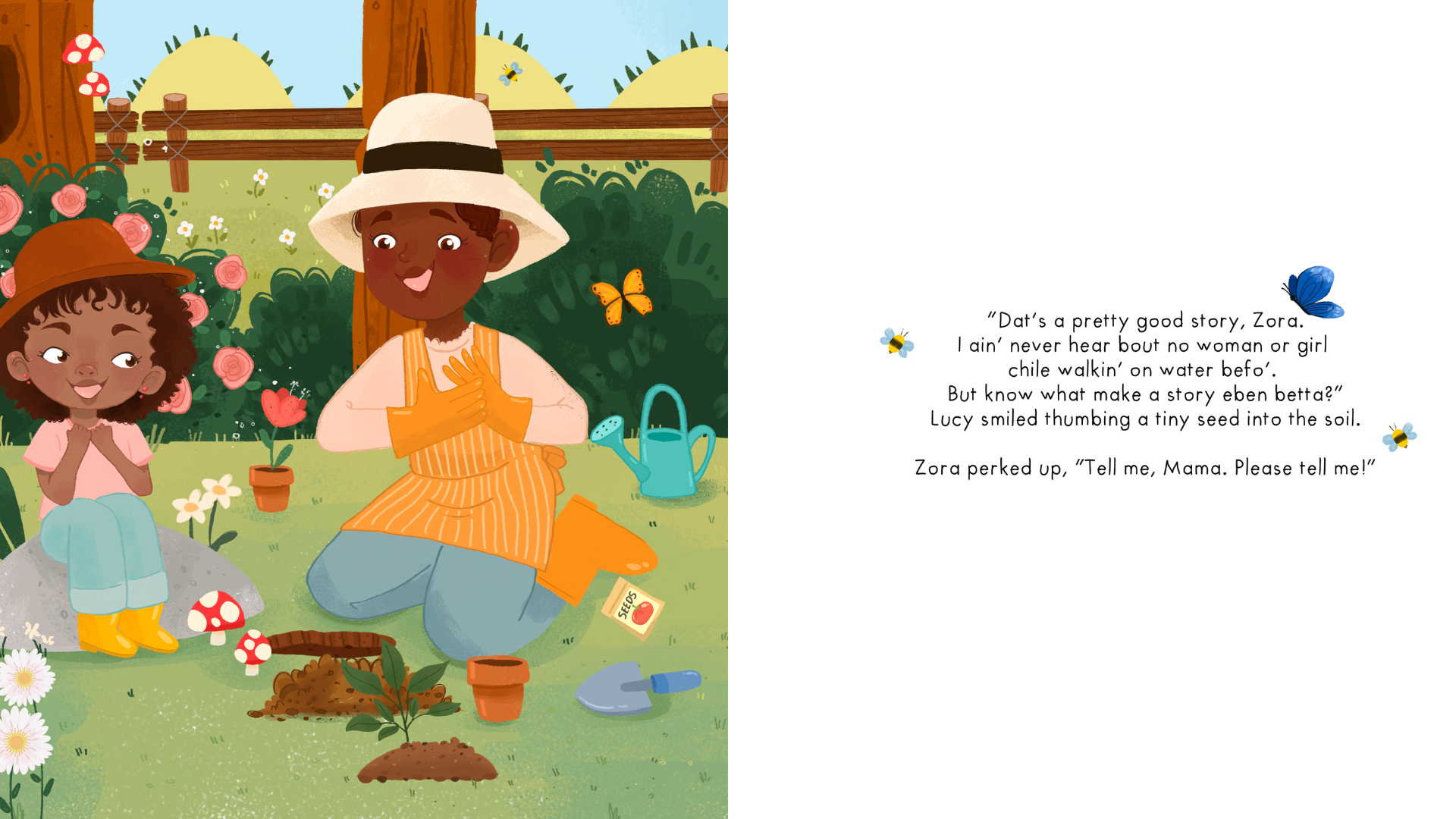

Zora’s Garden: Language

Language is central to Zora’s Garden. The story intentionally uses vernacular, commonly known as African American Vernacular English (AAVE), to honor Zora Neale Hurston and the linguistic traditions she fiercely preserved in her own work. Zora believed everyday speech carried beauty, history, and intelligence, and she fought to protect it on the page.

In Zora’s Garden, phonetic spellings and vernacular rhythms are used with care to reflect how language is spoken in real homes and communities. Zora’s mother speaks in vernacular, while young Zora does not. This choice was intentional. Much of Zora’s early knowledge, confidence, and imagination comes directly from her mother, reminding readers that wisdom is not determined by “proper” speech.

Too often, speakers of AAVE are treated as less intelligent or less capable. By placing vernacular language in the voice of a loving, guiding mother, the story honors a more authentic dynamic, one where knowledge, care, and authority are clearly present. This approach reflects Zora Neale Hurston’s legacy and her commitment to honoring Black language as a living, powerful inheritance.

It seems that he is unwilling to believe that a Negro preacher could have so much poetry in him…He must also be an artist. He must be both a poet and an actor of a very high order, and then he must have the voice and the figure.

—Zora Neale Hurston, 1934 Letter to James Weldon Johnson

Zora’s Garden: Mother-Daughter Relationship

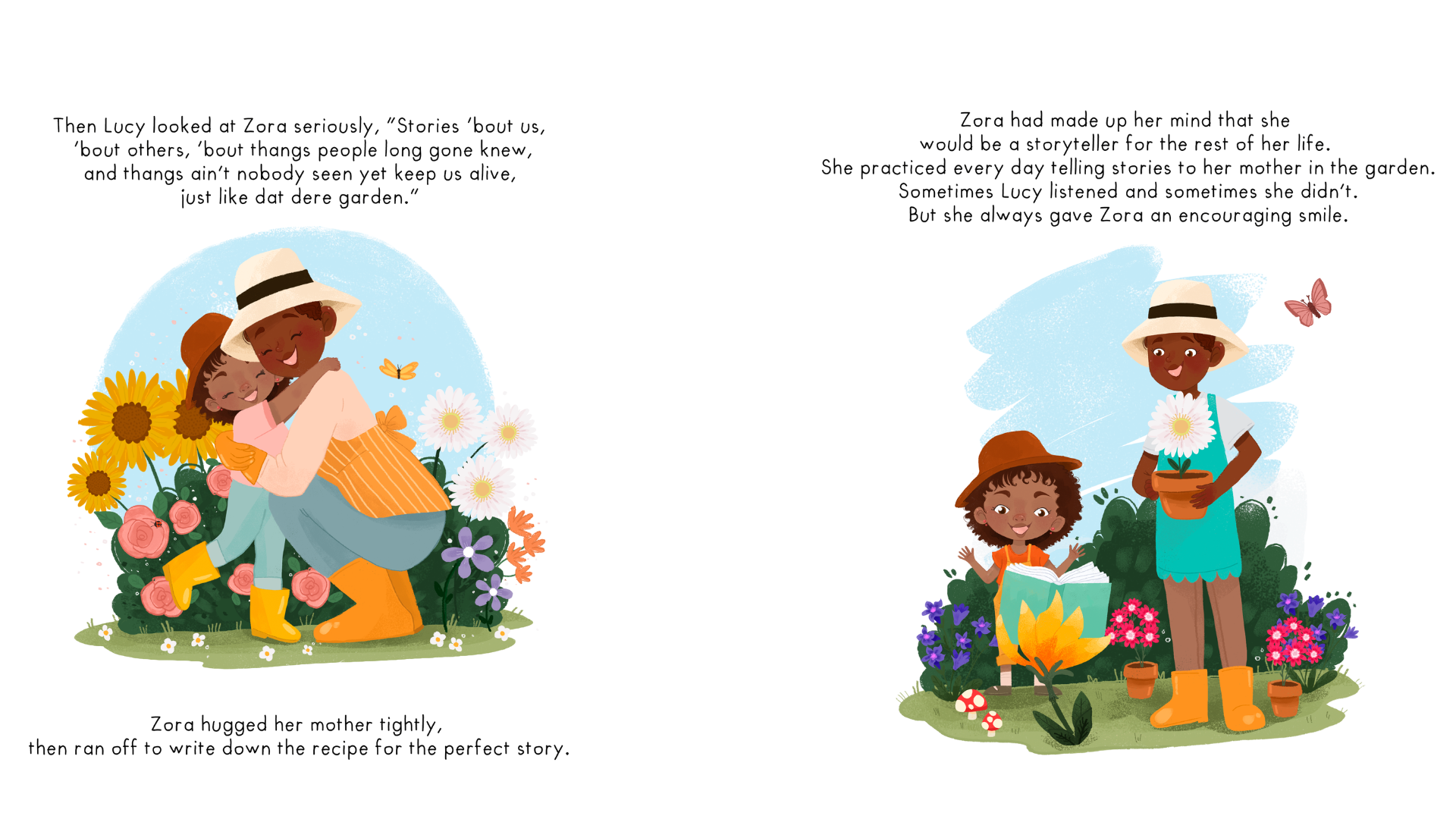

At the heart of Zora’s Garden is the relationship between Zora Neale Hurston and her mother, Lucy Potts Hurston, a bond that shaped Zora’s sense of self, imagination, and possibility.

Lucy Potts Hurston was Zora’s first protector and greatest advocate. She famously urged her daughter to “jump at the sun,” encouraging her to dream beyond the limits placed on Black girls at the time. Lucy also shielded Zora from forces that sought to diminish her spirit, including a father who Zora later said wanted to “squelch” her spirit, and a wider world that held narrow expectations for little Black girls.

Zora’s Garden honors this relationship with intention and care, recognizing that without Lucy Potts Hurston’s protection, belief, and guidance, there would have been no Zora as we know her. By centering their bond, the story pays tribute to the unseen labor of mothers and grandmothers whose love and courage make brilliance possible.

Mama exhorted her children at every opportunity to “jump at de sun.” We might not land on the sun, but at least we would get off the ground.

—Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road

Another time, I dashed into the kitchen and told Mama how the lake had talked with me, and invited me to walk all over it...Wasn’t that nice? My mother said that it was...Mama never tried to break me. She’d listen sometimes, and sometimes she wouldn’t. But she never seemed displeased.

—Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road

Zora’s Garden: Grief

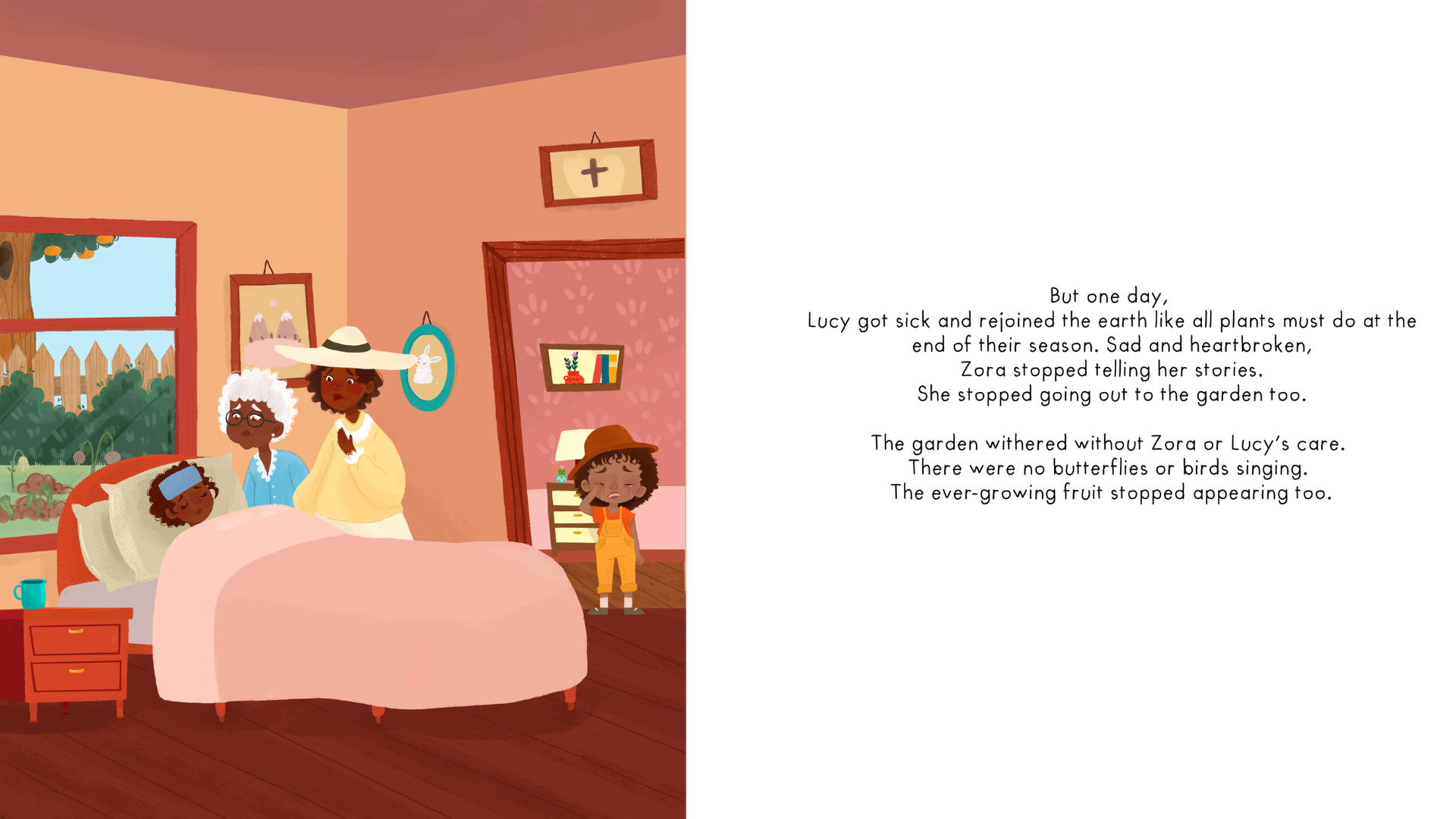

Grief is a quiet but important presence in Zora’s Garden. In the years surrounding the pandemic, many children experienced loss for the first time and were left trying to understand mortality, absence, and change.

The story honors Zora Neale Hurston’s own experience of grief. At just thirteen years old, Zora lost her mother, Lucy Potts Hurston, the most important person in her life. This moment marked a profound turning point for her, shaping how she moved through the world and how she carried memory.

In Zora’s Garden, grief is expressed through the language of the garden. When Lucy is gone, the garden withers. Stories stop. Birds fall silent. Fruit no longer appears. By using the garden as a mirror for loss, the story offers children a gentle way to understand grief as something real, painful, and deeply connected to love.

This approach allows young readers to see that sadness does not mean the end of growth. It honors one of the most pivotal experiences of Zora’s life while offering children space to name loss, sit with it, and eventually imagine what care and healing might look like after.

That hour began my wanderings. Not so much in geography, but in time. Then not so much in time as in spirit. Mama died at sundown and changed a world. That is, the world which had been built out of her body and her heart. Even the physical aspects fell apart with a suddenness that was startling.

—Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road