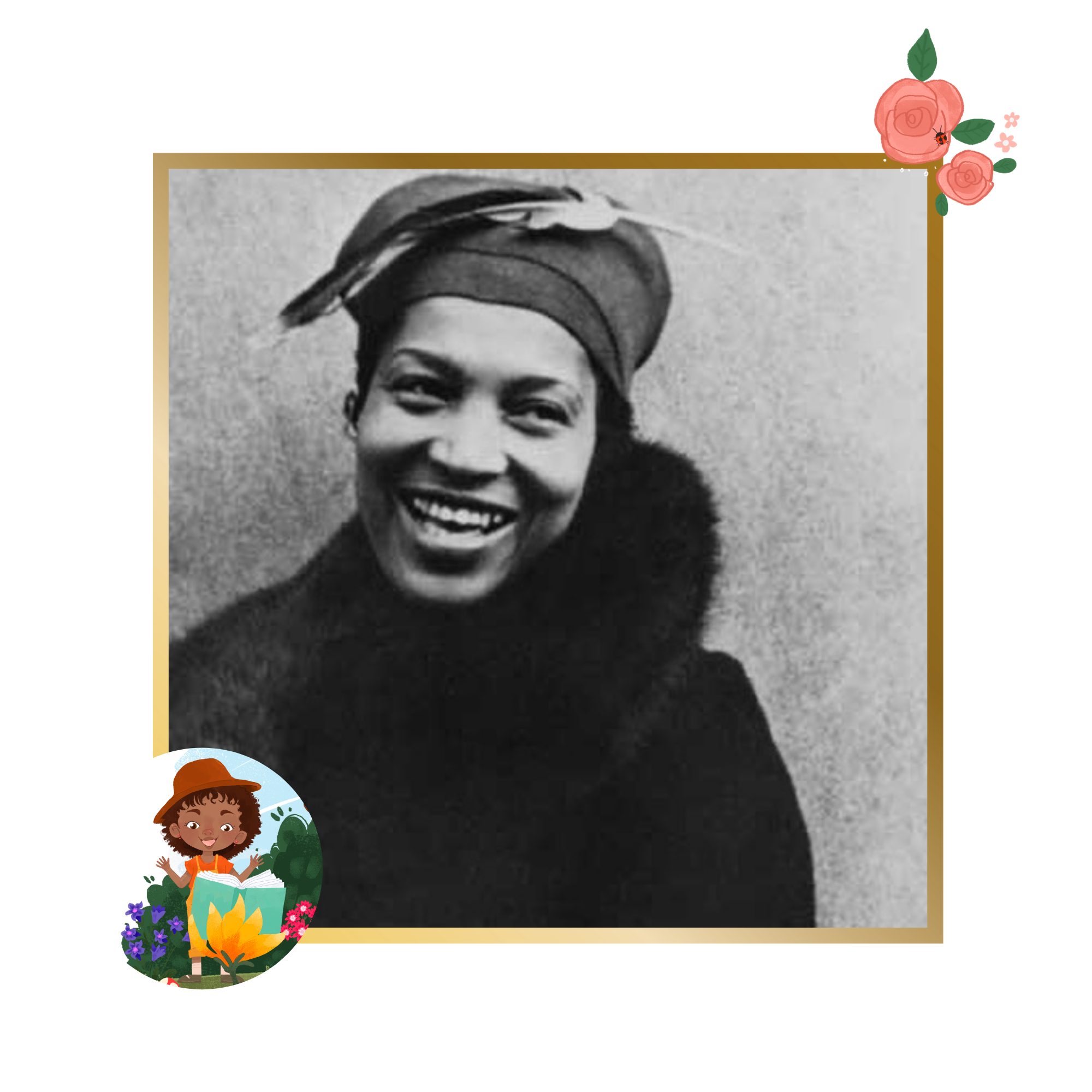

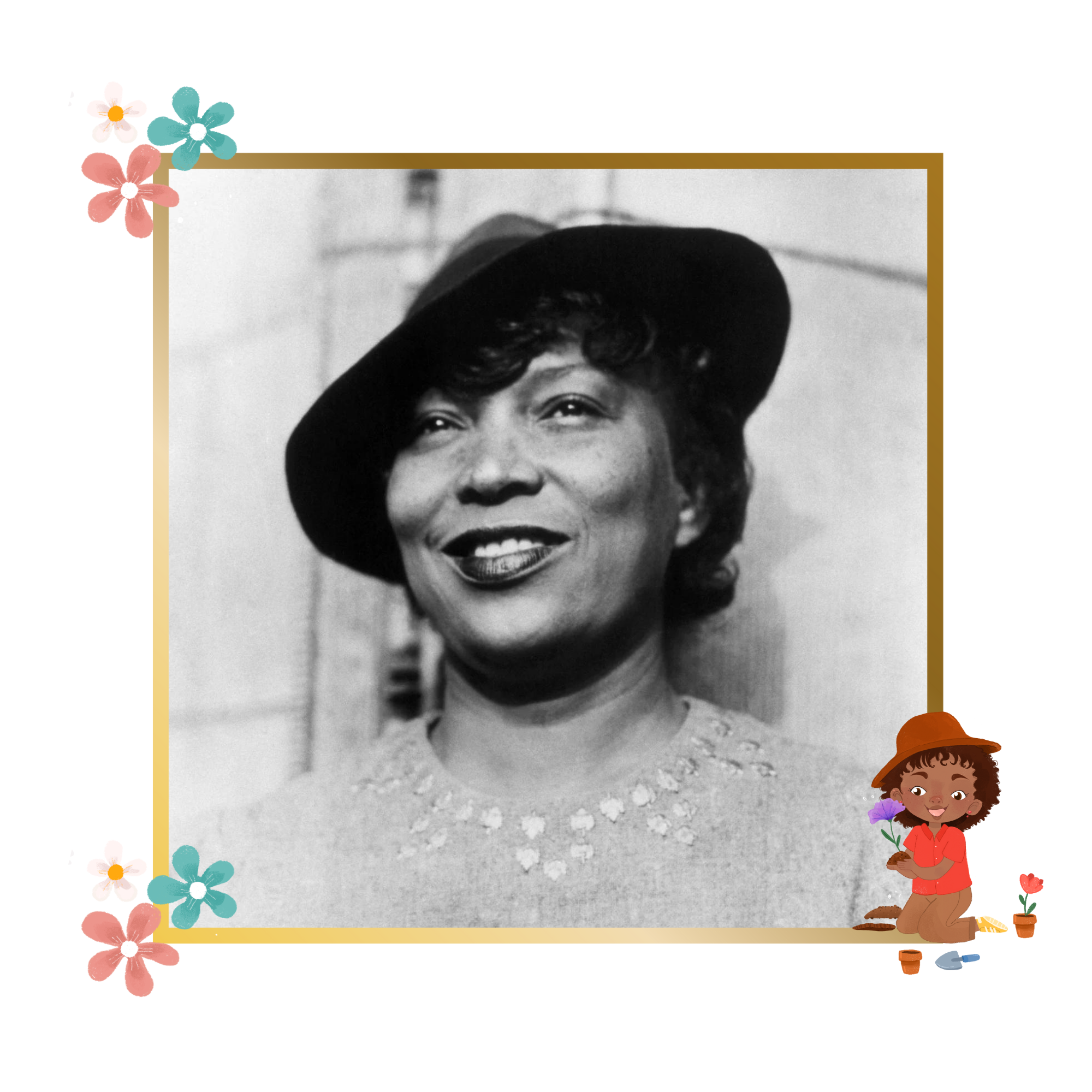

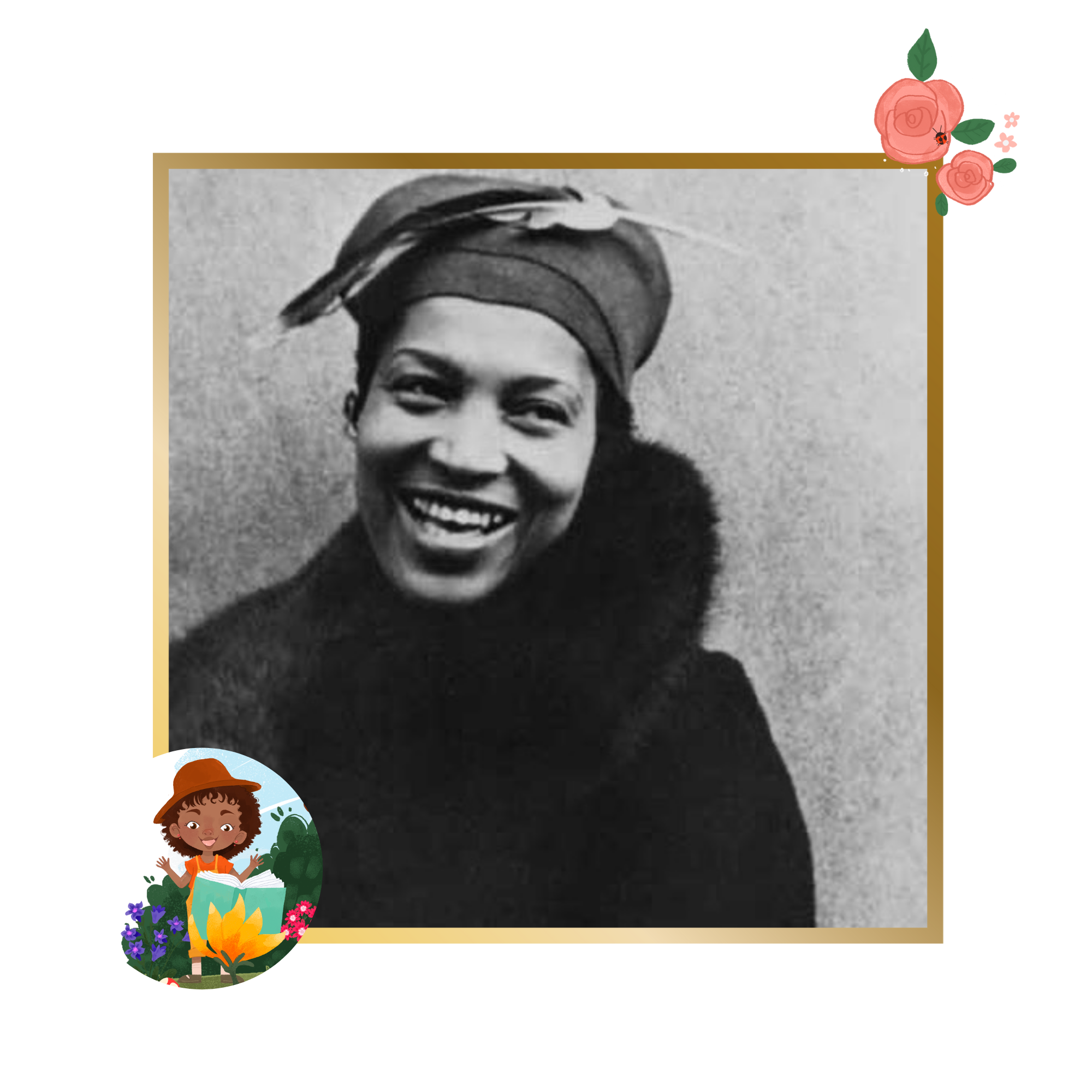

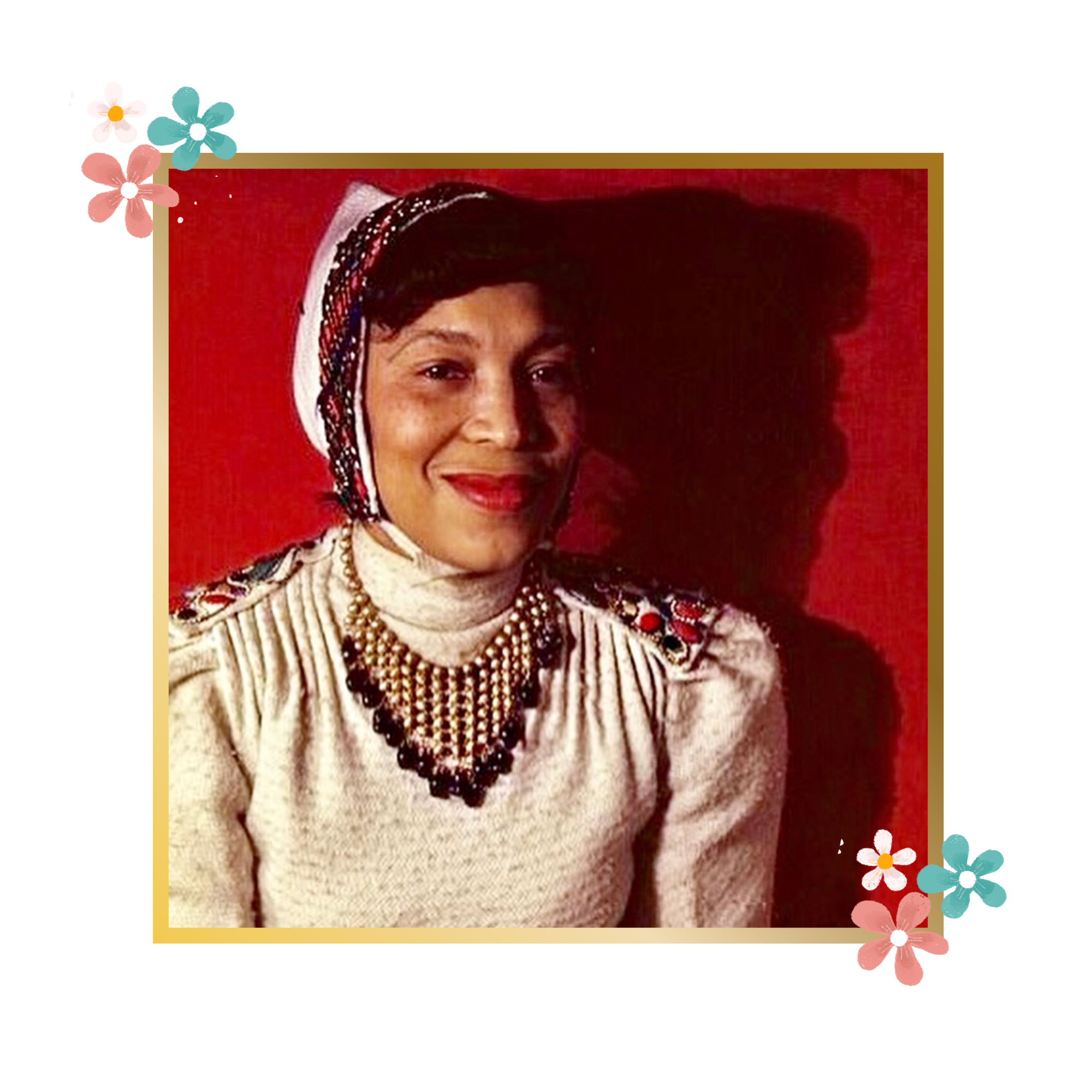

Zora Neale Hurston

“Mama exhorted her children at every opportunity to ‘jump at de sun.’

We might not land on the sun, but at least we would get off the ground.”

— Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road

The Woman Behind Zora’s Garden

So… Who Was Zora Neale Hurston?

If Zora Neale Hurston walked into a room, you would know it.

Maybe she would announce herself.

Maybe she would throw her head back in a boisterous laugh, proudly calling out the title of her award-winning play, Color Struck. Or maybe it would be her signature wardrobe that would draw your eye. Zora never tiptoed. She did not whisper. She arrived, always fully herself.

In fact, it was often said that even at a party, Zora was the party.

She could stop a room cold by playing her guitar or harmonica, or by breaking out into a folk song before launching into a story in her Southern drawl. Some of those tales came from her childhood in Eatonville, Florida. Others were gathered years later while she traveled the American South as a trained cultural anthropologist, collecting folklore, children’s games, work songs, and everyday wisdom. Stories of working people. Stories of children at play. Stories the world was never meant to forget, but would have if it weren’t for her.

Through her charm and wit, Zora became a mainstay in what would later be named the Harlem Renaissance. Bold, brilliant, and unapologetically Southern, she earned a reputation as its queen.

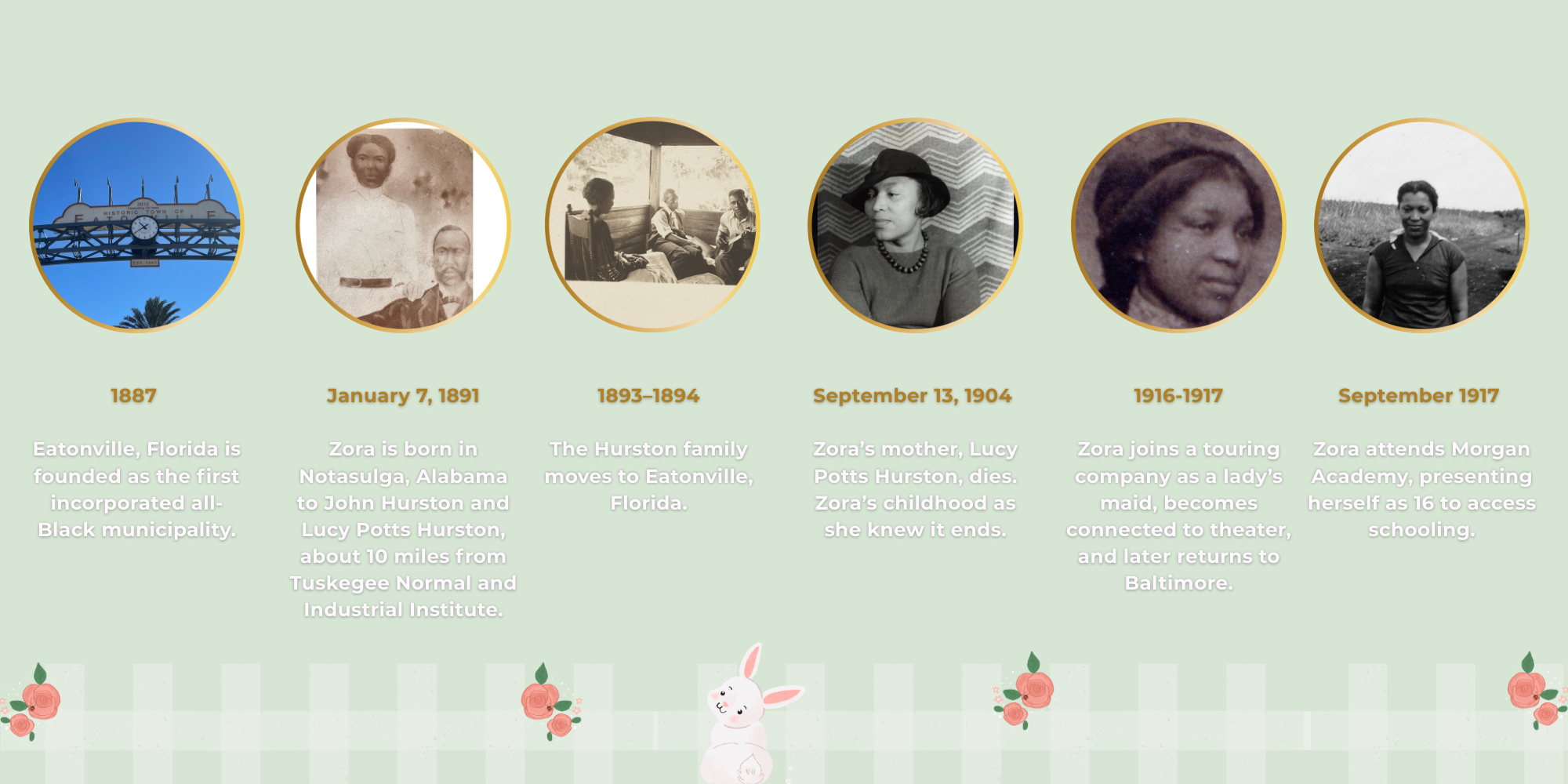

Where She Began

Zora Neale Hurston was born on January 7, 1891, in Notasulga, Alabama, about ten miles from Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. Though she was born in Alabama, Zora grew up in Eatonville, Florida, the first all-Black incorporated municipality in the United States.

She was the youngest daughter and fifth-born child among her eight siblings and part of one of Eatonville’s founding families, twice over. Her father, Reverend John Hurston, served as Eatonville’s mayor three times and helped write town laws that remain in place today. He was also the longtime pastor of Macedonia Missionary Baptist Church.

Zora grew up watching Black people govern themselves, tell their own stories, and live full, complicated lives, not only in the town itself, but inside her own home.

Her mother, Lucy Potts Hurston, came from a land-owning Black family in Alabama and worked for a time as a schoolteacher. Zora later remembered that her mother oversaw the children’s education until they moved beyond her own teaching capacity. After that, Zora’s eldest brother, Dr. Hezekiah Robert Hurston, affectionately called Bob, took over their schooling while Lucy continued to monitor their progress.

Only when the children were ready did they attend Hungerford Normal and Industrial School, the first school for Black children in Central Florida.

Lucy Potts Hurston believed fiercely in education and an entrepreneurial mind. Even more than that, she believed in imagination. She encouraged her children to think boldly, speak freely, and reach beyond what the world expected of them. That belief would shape Zora for the rest of her life.

Loss and Becoming

When Zora was just thirteen years old, her world shattered. Her mother died after a long illness that left her bedridden and frail. Zora remembered her sickness as an unrelenting “chest cold.”

With her mother’s death came the loss of protection and stability. Without her mother’s ingenuity and guidance, the Hurston family’s wealth and status began to dissolve. And the girl who had once been allowed to roam freely, to read endlessly, climb trees, and create imaginary worlds beneath her front porch, was suddenly expected to be quieter. Smaller. More in line with what a young Black girl was supposed to be.

Zora struggled to land on her feet after that. Still, the seeds had already been planted.

Education on Her Own Terms

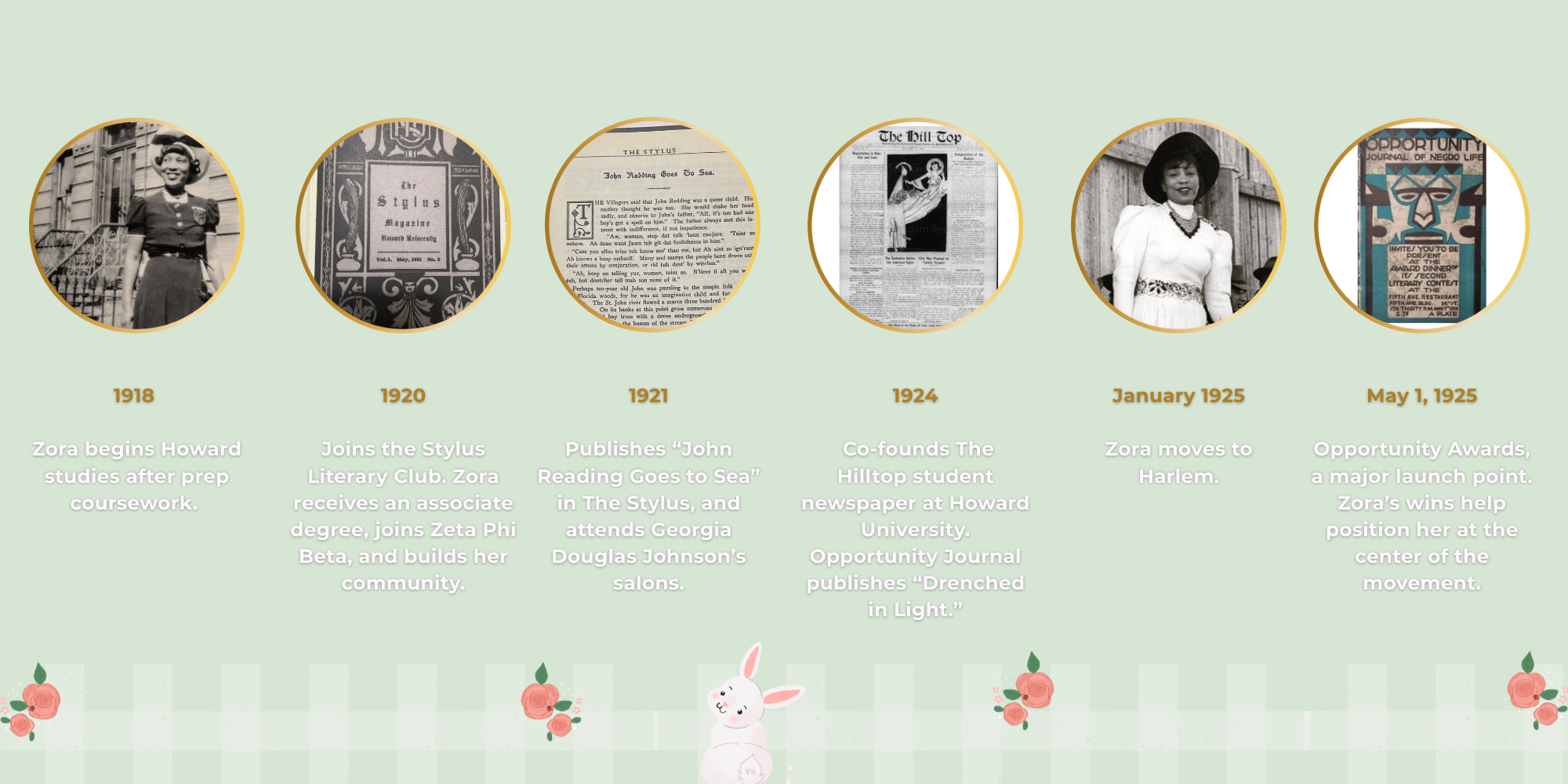

By her mid-twenties, Zora was determined to pursue education on her own terms. After working briefly with a Gilbert and Sullivan touring company as a ladies’ maid for the lead singer, she found herself unemployed and at a crossroads before long. Lucky for her, the job exposed her to the world of theater and Zora would stage plays and performances later in her life.

Struggling to maintain waitressing jobs and sell sundries out of her Baltimore boarding house, Zora decided to return to school, enrolling at Morgan Academy. To attend school for free, Zora shaved ten years off her age.

During that time, she learned about Howard University from her friends’ visiting cousin Helene Johnson, who told her she was “Howard material.” Though her schooling initially fell short of Howard’s requirements, Zora persisted. She worked, made up the required classes, and eventually enrolled at Howard University in 1918.

At Howard, Zora thrived. She joined the Stylus Literary Society, published her first short story, “John Redding Goes to Sea,” and co-founded the student newspaper, giving it the name The Hilltop. The paper still exists today as the oldest collegiate paper in the country. She also attended literary salons hosted by Georgia Douglas Johnson, where she met leading Black thinkers and artists of the time.

New York and the Harlem Renaissance

With the encouragement of leading figures, Zora left school and moved to New York City in January 1925. She arrived with $1.50 in her pocket and a suitcase so empty she packed it with newspaper to keep her belongings from rattling. What she did have was a lot of hope and talent. The National Urban League had published her short story “Drenched in Light” in its December issue as proof of her writing chops.

Just months later, on May 1, 1925, Zora won four awards at the National Urban League’s inaugural Opportunity Awards dinner. That night marked her arrival on the national literary stage.

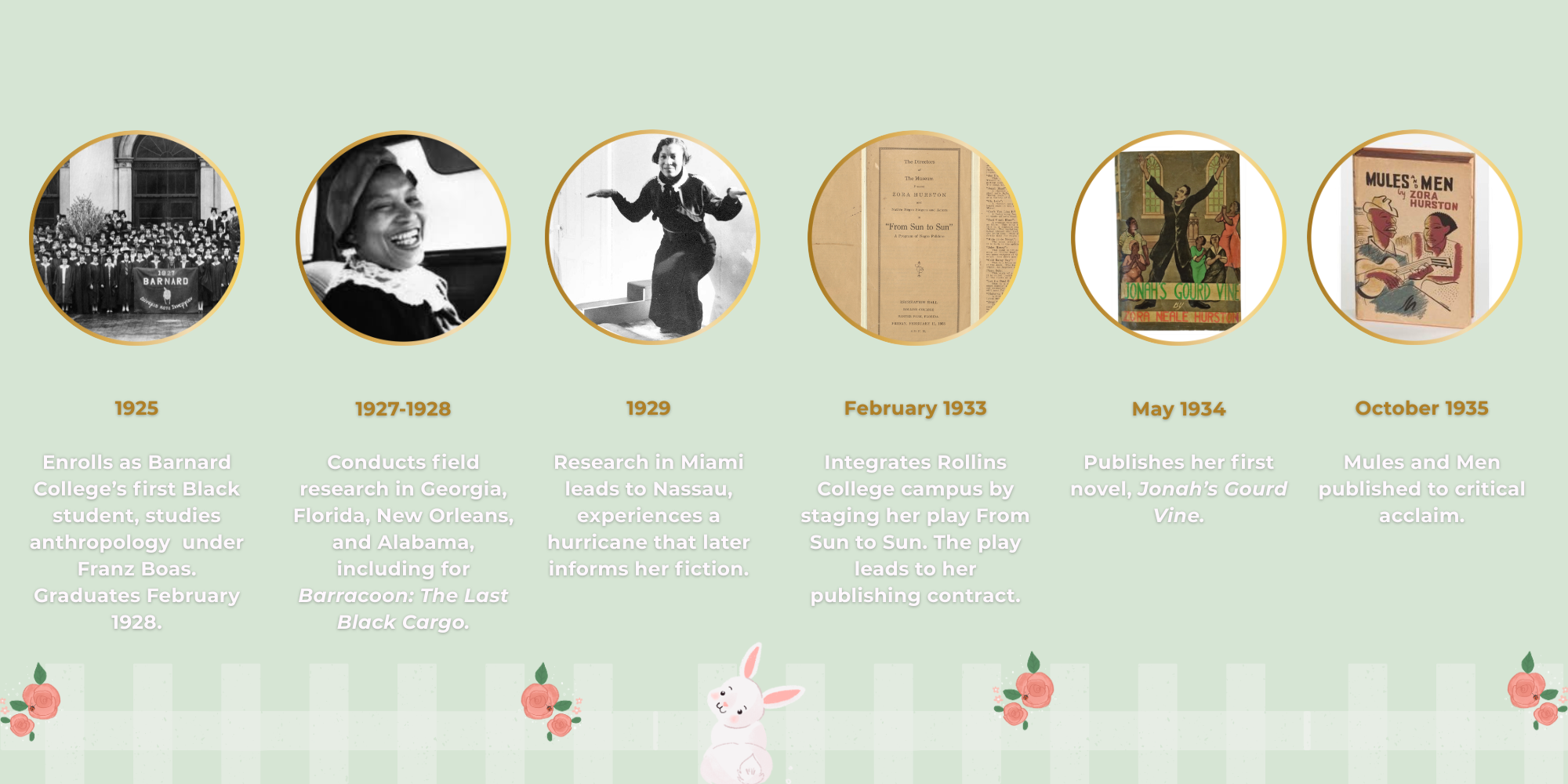

Later that year, Zora enrolled at Barnard College, urged on by a Barnard College board member who had attended the Opportunity Awards and believed it was time for the all-white college to be integrated. Zora became Barnard’s first Black student that fall.

While at Barnard, she studied under Franz Boas, the father of modern American anthropology. Though she graduated in 1928 with a degree in English, she was formally trained in anthropological methods that would shape her life’s work.

Fieldwork, Books, and Legacy

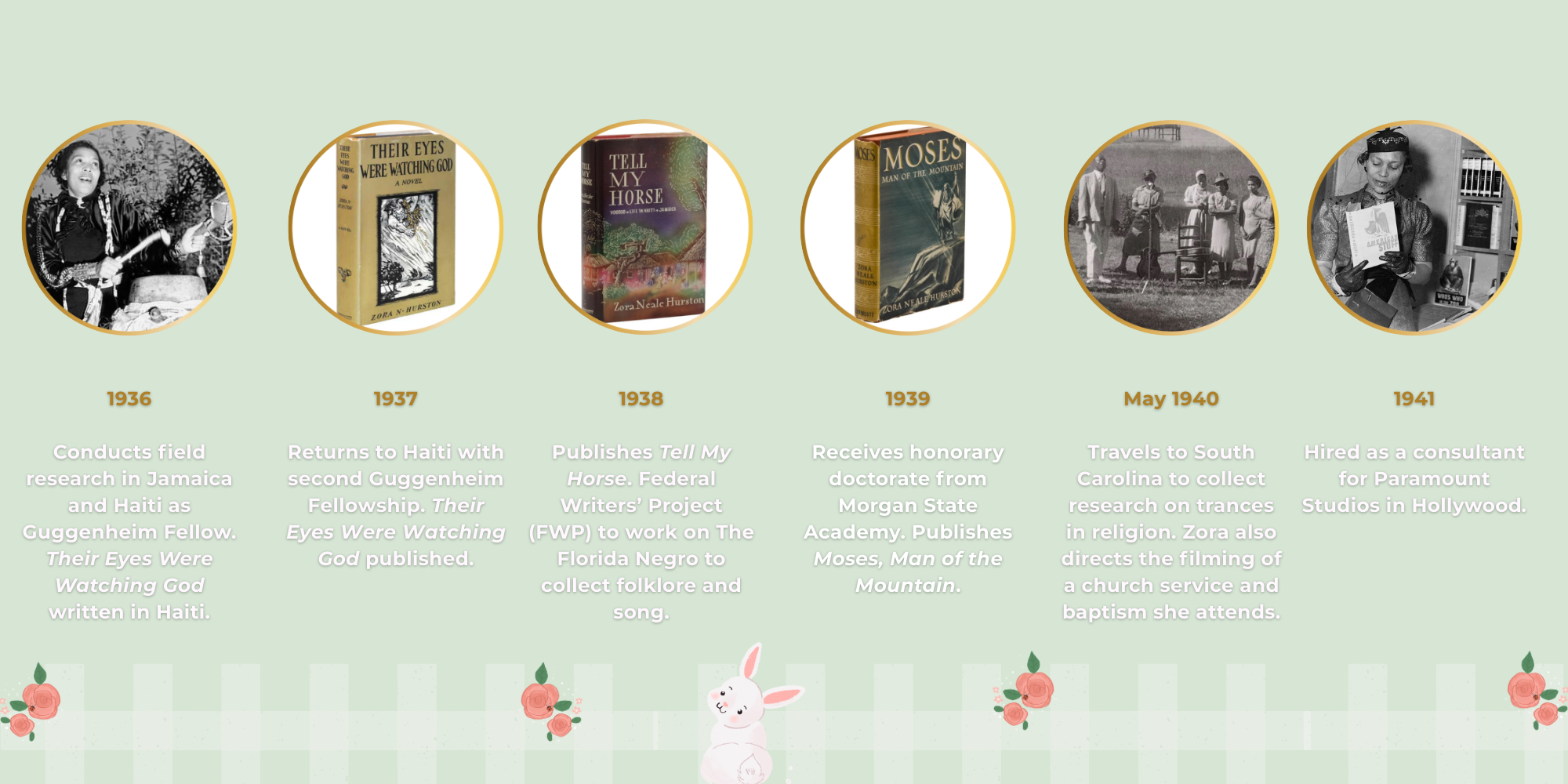

Shortly after graduation, Zora conducted research in Nassau. In 1936 and 1937, she traveled to Jamaica and Haiti as a two-time Guggenheim Fellow. While in Haiti, researching Vodou and other African-derived spiritual traditions often reduced to derogatory stereotypes, Zora wrote her most famous novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, in just seven weeks.

Throughout her life, Zora published seven books, including novels, folklore collections, and her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Roa*. She also worked as a playwright, journalist, short story writer, and anthropologist, all while struggling with financial instability and limited institutional support.

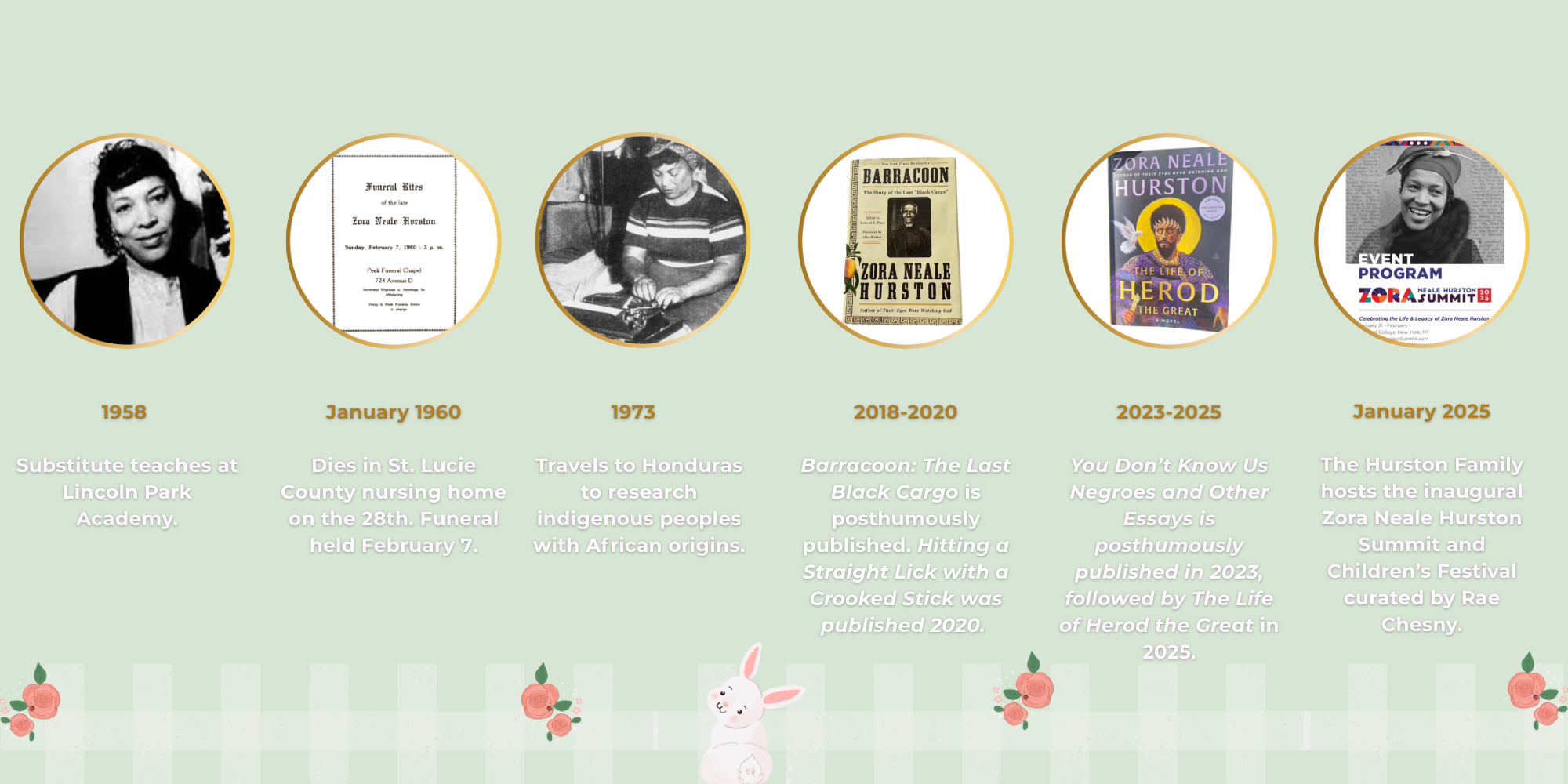

By 1958, Zora was living in Fort Pierce, Florida, where she worked for the Fort Pierce Chronicle and served briefly as a substitute teacher at Lincoln Park Academy. Her health declined, and she died on January 28, 1960. She was buried in an unmarked grave.

That changed in the 1970s, when novelist Alice Walker traveled to Florida, marked what she believed to be Zora’s resting place, and published “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston.” The essay reignited interest in Zora’s life and work.

Why Zora Still Matters

Zora Neale Hurston’s fierce devotion to truth, imagination, and the everyday people of the African diaspora continues to inspire writers, scholars, and artists around the world.

She is the literary ancestor whose spirit lives at the heart of Zora’s Garden, which the author hopes will expand her legacy to children, reminding them of the power of their voices, their stories, and their view of the world.